Logic and truth in economics

26 Nov, 2020 at 16:52 | Posted in Economics | 13 Comments

But that’s not the whole picture. As used in science, analysis usually means something more specific. It means to separate a problem into its constituent elements so to reduce complex — and often complicated — wholes into smaller (simpler) and more manageable parts. You take the whole and break it down (decompose) into its separate parts. Looking at the parts separately one at a time you are supposed to gain a better understanding of how these parts operate and work. Built on that more or less ‘atomistic’ knowledge you are then supposed to be able to predict and explain the behaviour of the complex and complicated whole.

In economics, that means you take the economic system and divide it into its separate parts, analyse these parts one at a time, and then after analysing the parts separately, you put the pieces together.

The ‘analytical’ approach is typically used in economic modelling, where you start with a simple model with few isolated and idealized variables. By ‘successive approximations,’ you then add more and more variables and finally get a ‘true’ model of the whole.

This may sound like a convincing and good scientific approach.

But there is a snag!

The procedure only really works when you have a machine-like whole/system/economy where the parts appear in fixed and stable configurations. And if there is anything we know about reality, it is that it is not a machine! The world we live in is not a ‘closed’ system. On the contrary. It is an essentially ‘open’ system. Things are uncertain, relational, interdependent, complex, and ever-changing.

Without assuming that the underlying structure of the economy that you try to analyze remains stable/invariant/constant, there is no chance the equations of the model remain constant. That’s the very rationale why economists use (often only implicitly) the assumption of ceteris paribus. But — nota bene — this can only be a hypothesis. You have to argue the case. If you cannot supply any sustainable justifications or warrants for the adequacy of making that assumption, then the whole analytical economic project becomes pointless non-informative nonsense. Not only have we to assume that we can shield off variables from each other analytically (external closure). We also have to assume that each and every variable themselves are amenable to be understood as stable and regularity producing machines (internal closure). Which, of course, we know is as a rule not possible. Some things, relations, and structures are not analytically graspable. Trying to analyse parenthood, marriage, employment, etc, piece by piece doesn’t make sense. To be a chieftain, a capital-owner, or a slave is not an individual property of an individual. It can come about only when individuals are integral parts of certain social structures and positions. Social relations and contexts cannot be reduced to individual phenomena. A cheque presupposes a banking system and being a tribe-member presupposes a tribe. Not taking account of this in their ‘analytical’ approach, economic ‘analysis’ becomes uninformative nonsense.

Using ‘logical’ and ‘analytical’ methods in social sciences means that economists succumb to the fallacy of composition — the belief that the whole is nothing but the sum of its parts. In society and in the economy this is arguably not the case. An adequate analysis of society and economy a fortiori cannot proceed by just adding up the acts and decisions of individuals. The whole is more than a sum of parts.

Mainstream economics is built on using the ‘analytical’ method. The models built with this method presuppose that social reality is ‘closed.’ Since social reality is known to be fundamentally ‘open,’ it is difficult to see how models of that kind can explain anything about what happens in such a universe. Postulating closed conditions to make models operational and then impute these closed conditions to society’s real structure is an unwarranted procedure that does not take necessary ontological considerations seriously.

In face of the kind of methodological individualism and rational choice theory that dominate mainstream economics we have to admit that even if knowing the aspirations and intentions of individuals are necessary prerequisites for giving explanations of social events, they are far from sufficient. Even the most elementary ‘rational’ actions in society presuppose the existence of social forms that it is not possible to reduce to the intentions of individuals. Here, the ‘analytical’ method fails again.

The overarching flaw with the ‘analytical’ economic approach using methodological individualism and rational choice theory is basically that they reduce social explanations to purportedly individual characteristics. But many of the characteristics and actions of the individual originate in and are made possible only through society and its relations. Society is not a Wittgensteinian ‘Tractatus-world’ characterized by atomistic states of affairs. Society is not reducible to individuals, since the social characteristics, forces, and actions of the individual are determined by pre-existing social structures and positions. Even though society is not a volitional individual, and the individual is not an entity given outside of society, the individual (actor) and the society (structure) have to be kept analytically distinct. They are tied together through the individual’s reproduction and transformation of already given social structures.

Since at least the marginal revolution in economics in the 1870s it has been an essential feature of economics to ‘analytically’ treat individuals as essentially independent and separate entities of action and decision. But, really, in such a complex, organic and evolutionary system as an economy, that kind of independence is a deeply unrealistic assumption to make. To simply assume that there is strict independence between the variables we try to analyze doesn’t help us the least if that hypothesis turns out to be unwarranted.

To be able to apply the ‘analytical’ approach, economists have to basically assume that the universe consists of ‘atoms’ that exercise their own separate and invariable effects in such a way that the whole consist of nothing but an addition of these separate atoms and their changes. These simplistic assumptions of isolation, atomicity, and additivity are, however, at odds with reality. In real-world settings, we know that the ever-changing contexts make it futile to search for knowledge by making such reductionist assumptions. Real-world individuals are not reducible to contentless atoms and so not susceptible to atomistic analysis. The world is not reducible to a set of atomistic ‘individuals’ and ‘states.’ How variable X works and influence real-world economies in situation A cannot simply be assumed to be understood or explained by looking at how X works in situation B. Knowledge of X probably does not tell us much if we do not take into consideration how it depends on Y and Z. It can never be legitimate just to assume that the world is ‘atomistic.’ Assuming real-world additivity cannot be the right thing to do if the things we have around us rather than being ‘atoms’ are ‘organic’ entities.

If we want to develop new and better economics we have to give up on the single-minded insistence on using a deductivist straitjacket methodology and the ‘analytical’ method. To focus scientific endeavours on proving things in models is a gross misapprehension of the purpose of economic theory. Deductivist models and ‘analytical’ methods disconnected from reality are not relevant to predict, explain or understand real-world economies

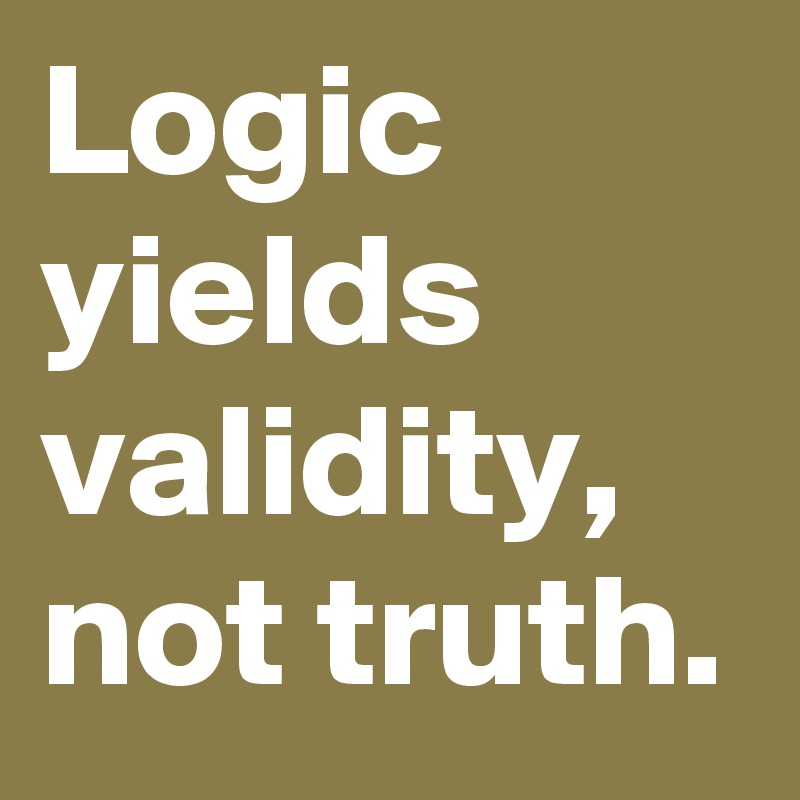

To have ‘consistent’ models and ‘valid’ evidence is not enough. What economics needs are real-world relevant models and sound evidence. Aiming only for ‘consistency’ and ‘validity’ is setting the economics aspirations level too low for developing a realist and relevant science.

Economics is not mathematics or logic. It’s about society. The real world.

Models may help us think through problems. But we should never forget that the formalism we use in our models is not self-evidently transportable to a largely unknown and uncertain reality. The tragedy with mainstream economic theory is that it thinks that the logic and mathematics used are sufficient for dealing with our real-world problems. They are not! Model deductions based on questionable assumptions can never be anything but pure exercises in hypothetical reasoning.

The world in which we live is inherently uncertain and quantifiable probabilities are the exception rather than the rule. To every statement about it is attached a ‘weight of argument’ that makes it impossible to reduce our beliefs and expectations to a one-dimensional stochastic probability distribution. If “God does not play dice” as Einstein maintained, I would add “nor do people.” The world as we know it has limited scope for certainty and perfect knowledge. Its intrinsic and almost unlimited complexity and the interrelatedness of its organic parts prevent the possibility of treating it as constituted by ‘legal atoms’ with discretely distinct, separable and stable causal relations. Our knowledge accordingly has to be of a rather fallible kind.

If the real world is fuzzy, vague and indeterminate, then why should our models build upon a desire to describe it as precise and predictable? Even if there always has to be a trade-off between theory-internal validity and external validity, we have to ask ourselves if our models are relevant.

‘Human logic’ has to supplant the classical — formal — logic of deductivism if we want to have anything of interest to say of the real world we inhabit. Logic is a marvellous tool in mathematics and axiomatic-deductivist systems, but a poor guide for action in real-world systems, in which concepts and entities are without clear boundaries and continually interact and overlap. In this world, I would say we are better served with a methodology that takes into account that the more we know, the more we know we do not know.

13 Comments

Sorry, the comment form is closed at this time.

Blog at WordPress.com.

Entries and Comments feeds.

In my view it’s a necessity to identify real social systems, created by humans, and build a corresponding model. Can we do so? Obviously when you look around social systems are always organizing human activities, not even theoretical or religious or philosophical or schools within natural science, nor ideologies, survive without some loose organizational structure. So how do you recognize social systems? They are created and perform different tasks, they have a mission, they have border against the surrounding environment and try to preserve their existence and adapt in order to do so.

But how does this correspond to individuals that actually are born active, don’t live in symbiosis with their mothers (Stern), relate to the systems, are they components within systems or should the systems be perceived from their functions? Individuals perceived to relate and take part in a functional capacity, not as components of the systems, driven to relate through inherent, biologically given social motivation (man a social animal). It’s a bit contradictory to common sense to see social systems from a perspective of what it does, from a perspective of material handling and information handling (like emotions), dependent on how individuals as systems in their own function, but in the real word of companies and other organizations it’s actually how you perform systems analysis!

Even tight families, filled with relations, emotions, motivation, values, activity may still be perceived functionally, for what is a family?

But this mean that Bertallanfys General systems theory perspective of hierarchies of systems and subsystems does not work as model to describe a society but networks of social systems, even stretching across land borders. The systems are related, they are open, and the individuals relate but are free agents and relate to many systems.

As human beings are intelligent creatures relations within systems cannot be described statically on an atomic level, but the system as a whole and functionally on a conceptual level and broken down to a certain degree is possible, functions, processes, IT applications, tasks, organisation, technology can be described on a meaningful level. Obvious examples are central banks, corporations, government, households, schools, credit systems, trade and capital flows etc.

The contradiction that Henry Rech above point to can only be resolved by pointing out that real, social systems exists and can be modeled and are not only a modeling perspective chosen by the analyst but a model trying to depict real, socialand human systems.

At least that is how I currently sees it. An obvious consequence is that that the believe in utility maximizing individuals and his or hers own interest drives how social system as markets and organisations work doesn’t hold though profit maximization, demand and supply etc is intact as describing different organisations as well as social systems guided by their interest as systems e.g. global power politics.

Comment by Lars B— 29 Nov, 2020 #

Obviously it’s also necessary to have a functionally oriented model of the human individual and how she relates to other individuals and corresponding functions within a social system, how the dual relationships workout and the functions within social systems are achieved through how individuals function.

As a model it can be falsified and different hypothesis about humans and social systems tested, but currently it’s not a properly tested theory.

Comment by Lars B— 29 Nov, 2020 #

A longish quotation that might please you, perhaps.

From Graeme D Snooks: Economics without time, Macmillan 1993

Can be downloaded free from https://booksc.xyz/

”Casual observation suggests that, throughout the social sciences,

abstract ideas are either more ‘respectable’, ‘successful’, or ‘popular’

than empirical accounts of reality. Why should this be so? The answer

throws modest light upon the problems facing the use of the social

sciences to understand reality and it may prevent society from taking

the least optimal development path. The primary objective of the social

sciences is to understand man in society, in the past, present, and

future. Its conduct is based upon the premise that there is an objective

reality that can be explored, albeit approximately; understood, however

imperfectly; and modified with difficulty. The major problem we

face is that the social activities of mankind are extremely complex,

interactive, and overwhelmingly difficult to understand through

observation alone. In order to make the intellectual task easier to

handle within the social sciences, the main activities of man in society –

economic, social, and political – have been isolated and subjected to

separate study; simple models of the various aspects of human society

have been developed; and techniques for handling empirical evidence

have been standardised. These abstract models serve a number of

functions: to sidestep the complexity of social reality by developing

persuasive ‘stories’ about cause and effect; to explore social reality so

as to create order out of apparent chaos; and, in conjunction with

historical analysis, to formulate ‘social’ policy. Theory, then, constitutes

the necessary (but not sufficient) tools to assist in the understanding,

and modification, of the present social reality.

The history of the social sciences has involved an intense struggle

between those who think that theory should be developed inductively

from observations of the past and present using historical and

statistical techniques, and those who believe that it should be

developed deductively with the aid of mathematics. In this struggle,

the inductionists had the upper hand until the mid- to late nineteenth

century, but thereafter the deductionists, through their impressive

development of abstract ideas – particularly in the discipline of

economics – began to surge ahead with, in Miltonian language,

‘blind zeal’ until they ultimately eclipsed the inductionists. The success

of the deductionists was so overwhelming that the social sciences have

become distinctly unbalanced in their approach to reality. Indeed,

there are even times when deductive theory is mistaken for – and

certainly preferred to – reality. In other words, in some circles, theory

in the social sciences has come to be regarded as a better guide to

reality than direct empirical studies of man in society. Policy in the

social sciences, for example, is normally derived directly from simple

theoretical models with little empirical analysis and no historical

insight. Apart from being a precarious procedure, it is highly

irresponsible, as human welfare is at stake. Social scientists, however,

are not alone in this; ecologists, who are determined to remodel

human society even more dramatically (despite their lack of expertise

in the social sciences), also base their policies on unverified deductive

models.

But what is it that accounts for the dominance of ideas, many of

them unsubstantiated, in the social sciences? My general argument,

which has been applied in more detail to the economics discipline in

Chapter 1, begins with the fact that the social sciences attract scholars

of two extreme types: those who prefer to explore worlds of their own

making – the ‘gameplayer’ in theoretical disciplines or the ‘mythmaker’

in history; and those who prefer to explore the real world – the ‘realist’.

Naturally there are rare individuals who can work brilliantly at both

ends of the spectrum, such as W. S. Jevons, the English neoclassical

economist, and there are a few more who feel happy in the role of

competent all-rounder; but the great majority tend to specialise at

either end of the spectrum. Needless to say, a sound social science

requires the application of both approaches: theory is required to make

sure that the right questions are being asked, and to isolate potentially

relevant relationships; while empirical/historical work is essential to

test the relevance of theory and to suggest modifications to it, to

suggest general causal relationships, and to provide a sound basis for

policy advice. But even more importantly, the role of history is to raise

and analyse the big issues that lie beyond the scope of economics –

issues concerning the forces that determine the very longrun processes

of economic change that are sweeping human society out of the past

and into the future. Economists merely focus upon the ripples that

briefly flit across the surface of these great waves (of 300 years or more

in duration) of economic change. But the tools of economists are

essential to historians who are attempting to analyse these forces. The

exclusion of either approach, therefore, will lead to the impoverishment

of the social sciences. Hence the fact that the triumph of

deductive theory has marginalised empirical/historical work in the

social sciences is cause for considerable concern. This concern, as it

relates to the discipline of economics, is a central message of Economics

without Time.

The imbalance between ideas and empirical work in the social

sciences, which has occurred rapidly during the last hundred years,

owes much to the fact that theory in the social sciences is viewed both

as more intellectually respectable and more effective in maximising

publications, and hence the reputation of the social scientist, than is

empirical work. The academic journals in economics, for example, are

dominated by minor theoretical issues that appear to have little or no

relationship to reality. In many cases this work is no more than an

intellectual exercise; no doubt quite ‘clever’ but, none the less, a mere

game. This is elaborated in greater detail in Chapter 3.”

Etc

Comment by Jan Wiklund— 28 Nov, 2020 #

Mathematics is only a language, as my late friend the mathematician used to say. It doesn’t tell if it is true or not.

I believe Bertrand Russell said something of the same kind a hundred years ago. I wish more mathematicians could be so outspoken.

Comment by Jan Wiklund— 28 Nov, 2020 #

A lot of mathematicians I have met are generally unimpressed by the maths economists use and can’t understand why economists insist on using it.

Comment by Nanikore— 29 Nov, 2020 #

Yes, my friend was also. In fact, the postgraduate students came to him to ask for a mathematical formula of their ideas, which he readily produced. Upon which they believed that he had proved that they were right.

He was very scornful about their gullibility.

Comment by Jan Wiklund— 29 Nov, 2020 #

“Necessary and sufficient” have something to do with analysis; it is not enough to break things down or simplify — the idea of analysis is to seek what is essential. This mainstream economics for all its mathematical show conspicuously fails to do especially with regard to its most fundamental postulates.

Comment by Bruce Wilder— 28 Nov, 2020 #

Dear Professor Syll,

Would you please check and see whether this yields your expected “revolution that will make economics an empirical and truly pluralist and relevant science?

On the Rediscovery of Economic Justice and Hoarding, at https://1drv.ms/w/s!AgFxYQBpjmMFgeQM9ZpQ_hiwZ4COxA?e=U0VeOh

Comment by Carmine Gorga— 27 Nov, 2020 #

I want to thank you, Dr. Syll, for the recent set of posts (perhaps they should be called guideposts) illuminating the issues with today’s mainstream economics.

Pointing back to some of your prior writing–and the work of others–has been illuminating for this non-academic interested party.

Comment by bruceolsen— 27 Nov, 2020 #

Lars writes:

.

“The world we live in is not a ‘closed’ system. On the contrary. It is an essentially ‘open’ system. Things are uncertain, relational, interdependent, complex, and ever-changing.”

.

“The world in which we live is inherently uncertain and quantifiable probabilities are the exception rather than the rule.”

.

“If the real world is fuzzy, vague and indeterminate…”

.

“What economics needs are real-world relevant models and sound evidence.”

.

If Lars’ first three statements are valid then I cannot see the point of pursuing the approach in his fourth statement and economics as science can only but be abandoned.

.

Comment by Henry Rech— 27 Nov, 2020 #

I would proffer that economics needs to be a rigorous multidisciplinary soft science that when applicable uses royal science to forward the endeavor that rises above petty political influences. So much of what has gone wrong with the endeavor is attributed to the latter with a side of path dependency baked in E.g. since covid it seems a few Mea Culpas are being staged for PR optics.

.

Balian of Ibelin:

What do we do?

Angelic Priest:

Convert, repent later.

Comment by skippy— 27 Nov, 2020 #

Real-world-relevant models include the Fed as ultimate insurer of large-volume more-or-less fully-hedged financial bets.

.

“By expanding and extending the asset-purchase programme, the Riksbank is making it clear that comprehensive monetary policy support will be available as long as it is needed,” the Riksbank said in a statement.

.

https://www.reuters.com/article/sweden-cenbank-rates/update-2-swedish-central-bank-adds-23-bln-to-qe-as-second-pandemic-wave-hits-idUSL8N2IC1TH

Comment by rsm— 28 Nov, 2020 #

Distribution is as always key and in my opinion no different to Milton’s push for a 2% targeted IR [natural] with a connotation of structural un-under-employment rate to facilitate the notion of sound money. As if money proceeds all outcomes from an A political methodology of social organization.

In addition I disagree with the proposition of the term – Real – from a Etymology stand point.

Comment by skippy— 28 Nov, 2020 #